Is it becoming harder for international firms to avoid tax?

Facebook’s decision to start paying more tax in the UK suggests that multi-nationals may be beginning to bend to public pressure.

It follows Google’s agreement with the UK’s HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) to pay £130m in back taxes.

But if Facebook’s eventual tax bill is similar in size, public pressure is unlikely to be satisfied.

Jonathan Isaby, chief executive of the UK’s TaxPayers’ Alliance, said: “The fact that Facebook has taken a voluntary decision to change its structure so it pays more Corporation Tax just goes to show how absurd the system has become.”

The problem, as most campaigners see it, is the system rather than the players.

Mr Isaby said: “The outdated tax system is simply not suitable for the modern, global economy and leaves the tax liabilities of multinationals open to honest dispute.”

Facebook has said that it has restructured its business to reflect the “value added” created by its UK workforce.

“Value added” is a crucial term because the consensus among tax authorities is that tax must be paid where value is created.

By admitting it creates value in the UK, Facebook admits it must pay tax in the UK.

One reason why Facebook decided to step into line may well be because UK tax rules have been changed.

The “diverted profits tax” came into effect in April 2015

Last year Chancellor George Osborne already instigated his “diverted profits tax”.

HMRC says this new tax is aimed at capturing tax from organisations that shift their profits to different jurisdictions to pay less tax.

That tax is set at 25%, higher than the 20% charged under UK corporation tax rate.

It is almost certain that Google and Facebook would have been hit by this tax, and may well have considered it cost effective to allow more profits to come within the scope of the UK’s corporate tax regime.

HMRC meanwhile says “all multinationals pay the tax due under UK law and we do not settle for a penny less.”

In reply all multi-nationals would doubtless agree with Google Europe boss Matt Brittin’s mantra: “Governments make tax law, the tax authorities independently enforce the law and Google complies with the law.”

But critics argue the law is not good enough.

And there are signs that more radical change is afoot.

In January, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) successfully brokered an agreement designed to improve the current system.

All 31 of its member countries have agreed to share information on the tax international firms pay, leaving them less room for moving their profits into low tax jurisdictions.

But the plan would still require implementation at national level.

If companies’ tax affairs are open to public scrutiny it could help to force change, experts believe

At the heart of the agreement is the concept of transparency, in particular what is known as “country-by-country reporting”.

This would force companies to tell the tax office of each country in which they operate, how many staff they employ there, what their revenues and profit are and how much tax they pay.

The European Commission has proposed EU member states do the same. If its plan is approved, it could eventually be turned into law by individual countries.

However it faces major hurdles – direct tax measures have to be voted in unanimously by all EU states.

Transparency

With transparency there’s a question of degree: is country-by-country reporting only for the eyes of the tax authorities in each country, or for everyone?

The Commission will publish a report on the question in the spring.

Richard Murphy, professor of international political economy at London’s City University believes public scrutiny is vital.

“If multinationals feel that they are out of the public eye, then they feel they can carry on the same way with the tax authorities – and nothing changes.

“It is only by having their affairs in the public eye, when everyone can see the choices they are making and the press can have a field day, that you have behavioural change.”

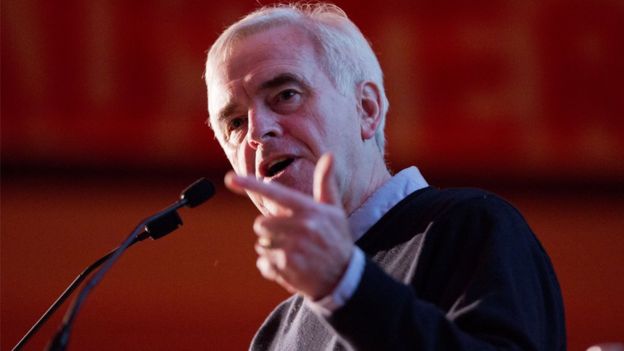

Labour’s John McDonnell called for the government to explain how it agreed the deal with Google

The prospect is already making investors nervous, according to Prof Murphy:

“Investors are crucial to this. They are beginning to question which companies are free-riding. If there is public scrutiny of their accounts that represents a real risk, it could result in a real change in perception of those companies.”

Momentum appears to be building behind this idea.

Even the UK government, having been criticised in the past for dragging its feet on the issue, has come out in favour of full transparency, with the chancellor telling the Financial Times he would like to see tax information made public – so long as it can be agreed multilaterally.

Business concerns

However some in the business community are worried.

“We recognise need for greater transparency and we share the common objectives to tackle fraud and evasion,” says James Watson of the lobby group Business Europe which represents national business associations such as France’s MEDEF and the UK’s CBI.

“But we are concerned at initiatives that might make the EU a forerunner and create a competitive disadvantage.

“If companies feel they have to reveal more information, and information that is commercially sensitive, that might damage the EU as an investment destination if the EU were to go ahead unilaterally.”

For some, though, even the powerful incentive of greater transparency doesn’t go far enough – they are calling for a complete overhaul of the system and the introduction of “unitary taxation”.

Unitary taxation

This is a more radical solution to the problem that beset the UK while trying to tackle Google’s tax affairs.

Companies’ tax arrangements have led to several public protests

Google – and Facebook – claimed that all their sales came out of Ireland, with the UK representing one of many marketing operations, and that it therefore made very little taxable profit in the UK.

But unitary taxation would see a company, however big, and however diverse, as one unit with one base and one profit.

Once the revenues and profits are added together they would then be broken down to represent the interests in each country, and the company would be taxed according to its activities there.

The European Commission has proposed a unitary tax system called the Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base (CCCTB). The US and Canada already have a form of unitary taxation for their corporations’ domestic profits.

Sol Picciotto, emeritus professor at Lancaster University Law School, says treating multinationals as single entities makes sense, but that it can be difficult for countries to agree on how they work this out.

The most obvious formula, he believes, is to base taxation of profits on where a firm’s assets, employees and sales are located.

“I think there must be some kind of change.

“The direction must be towards treating multinationals as single entities. Up until now they have been seen as a collection of independent entities, and I think that is a mistake,” he says.

Not everyone agrees. The Tax-Payer’s Alliance says: “The unitary taxation approach is hugely complex and would be hugely distortionary, as the extent to which value added can be attributed to assets, labour or sales varies greatly between industries.”